Learn Blues Piano Styles

From the old stories to the new styles, learn blues piano in this guide based on the Blues You Can Use class.

Have you always wanted to learn blues piano?

If you’ve been curious about learning blues piano for beginners, you’ve probably noticed that some blues piano lessons seem to be shrouded in secrecy. In jazz and blues professionals, there is often an air of “you should already know this,” and little information for beginner piano blues piano players. Often these professionals will play flashy blues piano riffs, and not explain the basic details of learning to play a blues.

I created the class Blues You Can Use as a way to break down barriers to access that make learning blues and jazz traditions inaccessible. I wanted a space where anyone could approach learning blues piano styles for beginners, and a space where the contributions Black blues musicians and women blues musicians would be celebrated. Most collegiate level jazz and blues classes will center the narrative on rules put in place by white men who are household names in the industry. I wanted to be able to highlight the roots of this style, and the Black women and men that created these traditions. It’s so important to make blues piano styles accessible to learn, because the blues is the foundation of all contemporary American music.

Learn how to play blues on piano in the self-study BLUES AND JAZZ YOU CAN USE course! Join the waitlist now to get a special discount.

What is a blues?

Nearly every style of American music draws roots from the African diaspora. I want to open this guide by acknowledging the Black Africans and Americans that made this music in history, and that are continuing to shape a legacy of music today. This credit is especially important when talking about blues, which is the backbone of American styles of music including rock, country, jazz and everything outside and in between.

So what is a blues? Blues music utilizes a simple musical structure that is the foundation of learning blues piano styles. Once that structure or form is internalized, it can be built out and developed further. The blues is a lineage of cultural stories and messages, and almost every musician attempting to describe what blues music sounds like will tell you that it is somehow the saddest story you’ve ever heard paired with the sweetest sound. Classic elements of blues music include spoken word or distorted singing paired with intentional dissonance. Blues music is rife with lowered pitches and deep, uneven rhythms. Blues music is a practice of creating music and reimagining what that music can be every time that you play it.

So here is a lil' snapshot of blues, of the scratchy back porch and the pops on the record, of the smell of an old flannel shirt and the sound of metal on metal. Blues feels like a chilly morning or a warm evening, it is smokey and sweet and bitter and good. Blues has preserved stories through oral tradition that would have otherwise been lost, and write both a love letter and a confession in one stroke.

The origins and history of blues music

Blues music originates from an intersection of work songs and spirituals, the crossroads of West African traditions and settler folk tunes. These styles of music the pre-date the blues were a musical patois, the English words and Christian messages sang with rhythm and form utilized in West Africa. The earliest blues were played on banjo, guitar, and jug band “found” instruments, because these were what were available, what could be played alone or with others, and instruments that were similar enough to some instruments used in West Africa to be easily learned and utilized.

Qualities of Blues Music

One of the clearest examples of West African musical traditions is call and response. This style of singing made music instantly accessible, singing the call and having the response returned to you by a crowd. This bypassed the need for writing music down, distributing it quickly and infectiously through this auditory practice. Call and response styles are still used in instrumental solo form in blues and jazz, and directly influenced the lyric form of the blues.

Early blues music styles often used a single line repeated 4 times. This evolved to the AAB lyric style, which often has a question or problem introduced in the A section, and the answer, or worsening of the situation in the B section. Blues, after all, is a style designed for venting, ranting, complaining, letting out all of the problems and the bad things that are happening. The lyric content evolved over time, and some blues have punchlines to a dirty joke or filthy, graphic lyrical content.

“The phrase "the blues" was written by Charlotte Forten, then aged 25, in her diary on December 14, 1862. She was a free-born black from Pennsylvania who was working as a schoolteacher in South Carolina, instructing both slaves and freedmen, and wrote that she "came home with the blues" because she felt lonesome and pitied herself. She overcame her depression and later noted a number of songs, such as Poor Rosy, that were popular among the slaves. Although she admitted being unable to describe the manner of singing she heard, Forten wrote that the songs "can't be sung without a full heart and a troubled spirit", conditions that have inspired countless blues songs.”

Social History of Blues Music

Music can never be separated from social context. It is social by nature, even when it is a personal or solitary activity, it is a reflection of a persons social environment and inevitably that music then affects the social environment by being played. Blues music was being played in the mid 1800s by Black people for Black people. This music would have been played in homes and in private spaces, and in pop-up style shows in Black communities. After the emancipation of slavery, Black musicians used music as one of a select numbers of skilled labor jobs that they were allowed to perform. Performing music was a way out of the labor jobs that were just an extension of the quality of life during enslavement. These early performances in venues and traveling shows were the beginnings of the blues spreading throughout America.

Unfortunately, part of the dispersal of the blues tradition is also due to the use of blues music in minstrel shows. Minstrel shows are a part of the deep rooted institutional racism in American music. These vaudeville style shows spread these styles of music as white performers dressed in blackface imitated Black people for humor. These shows have an ugly history, at some points even making Black people wear blackface and act in humiliating ways for the entertainment of white audiences. It is important to research American folk tunes to learn of their origins, or the original lyrics used, as some are authentic blues and others are horrifying derivations used in minstrel shows. These shows are likely the foundation of the popular late night comedy show today, as the early template for a comedic variety show. I say this not to cancel all music with these roots or to begrudge the format of the variety show, but to encourage everyone as a consumer of music and comedy to evaluate the origins and to hold performers to high standards in the music they choose, the jokes they make, and the people they higher.

The emancipation of slavery lined up very closely with the invention and development of recording technology. Approaching the turn of the century, this new technology allowed people to archive music as it was being performed, and to distribute music far and wide. Of course, fair pay and proper treatment were constant issues for recording musicians, and some of the earliest recordings were likely made without consent of distribution.

It’s no surprise that blues music ended up being forbidden in households, censored, with an emphasis being put on musicians doing the good thing and playing in church, not in nightclubs or on stage. That feeling of rule breaking, indulging in taboo, and rebelling against the system of one of the defining threads of styles of American music to follow. What is the point of jazz, rap, rock, or metal if not to shout a message that you were told to keep quiet?

Early Blues Sampler:

Bessie Smith

Ma Rainey

WC Handy

Lead Belly

Learn how to play blues on piano in the self-study BLUES AND JAZZ YOU CAN USE course! Join the waitlist now to get a special discount.

What are the different types of blues?

Country Blues

Country blues doesn't have anything to do with country music! Although country music might have something to do with country blues. Country blues is also known as folk blues, or downhome blues. This is pretty much the earliest iteration of the blues, using a blend of gospel styles and call and response forms common in West African folk music. Country blues is the foundation, the root of all blues styles to follow, and also the root of most American music. Every style to develop since has drawn influence from elements of these country or folk blues.

I like to imagine country blues as a quilt of musical histories and traditions- and the picnic blanket gathering place for the music to follow.

Country blues sounds like low hollers and sparse singing. It’s home grown, and corrugated like a washboard. The fingerpicking guitar is easygoing, and the lilting words are like the rambling story that always has a moral at the end. Elements of country blues include voice and guitar, sometimes a pre-ragtime or boogie types of blues piano styles with lots of boom-chuck patterns. Country blues usually features simple melodies. If these early blues styles weren't originally scratchy and distorted, the turn of the century recording technology has made sure we'll remember them that way!

Country blues isn’t about country music, it’s really the folk origins of blues style. It’s sittin’ on the back porch and making music that reflects how you feel, or reaches for something just out of grasp. It’s played on whatever instruments are available- usually a guitar and a voice. That’s it.

Country Blues Sampler:

Bessie Tucker

Willie Johnson

Irene Scruggs

Muddy Waters

Blind Lemon Jefferson

Jessie Mae Hemphill

Victoria Spivey

Robert Johnson

Sippie Wallace

Leadbelly

Delta Blues

The delta blues is not so different from country blues, but they have a special regional style that sets them apart from other variations. The Delta blues is associated with the southern region of the US that lies along the Delta river.

This style is usually played with guitar, usually slide guitar, and sometimes even electric slide guitar. Harmonica is another instrument prevalent in this style. The Delta blues still use a ramblings style of lyrics that tell a story, usually humorous or with a moral at the end.

Delta blues styles have a distinctly metallic sound, created by the crystalline sounds of the slide guitar and the breath of the harmonic. Delta blues are a close cousin of swamp jazz, and are really gritty and true. There's no polish or allusion in this style- just raw and honest stories and sounds. Like the country blues, a delta blues will ramble on, passing a lineage of stories and pausing, breathing throughout so you can really take it in. The twang is in the guitar, sure, but even more in the voice. This is a distinctly southern style of playing, singing, and story telling.

Exploring musical styles is so interesting, because these styles evolved without categorization. With the perspective of hindsight, we can say that most blues originating in the delta region featured these instruments and this style, but music just flows, and people play together and pass ideas between friends and different bands. It's so fun to put this blues playlist on and listen to the blues style as it migrates and evolves.

Delta Blues Sampler:

Memphis Minnie

Mississippi John Hurt

Geeshie Wiley

John Lee Hooker

Rosa Lee Hill

Elvie Thomas

Bertha Lee Pate

Big Joe Williams

Robert Night

Chicago Blues

The style of Chicago blues is a part of the category of "urban blues," including Detroit, St. Louis, and Dirty Blues. Yes, dirty blues is a whole genre of its own! I like to think of the Chicago blues as the electric genre, because these urban styles are linked with the ability to amplify sound and mic voice and guitar.

This is also the style that really integrates the piano into the style of blues music. Unlike the other styles of blues described above, the Chicago blues is less about the guitar and more about the voice and other accompanying instrument, including guitar and oftentimes drum set. Chicago and urban blues often have women as the singers.

By adding piano and drums, the rhythmic feel of this style changed from the earlier styles, often creating a more driving percussive feel. The blues piano styles evolved in Chicago blues, turning some boom-chuck patterns from the country blues and early ragtime into driving shuffles and swinging boogie style basslines. These patterns of blues piano playing laid the foundation for piano's role in rock and roll music to follow, and modeled early comping styles to be used in jazz as the genres progressed.

This is also one of the earliest places to hear electric sounds in the blues, and the distinct sound of a voice sang through a microphone, or an amplified electric guitar is one of the qualities that differentiates these urban blues from the earlier styles heard in the south.

Chicago Blues Sampler:

Ma Rainey

Alberta Adams

Buddy Guy

Howlin’ Wolf

Karen Lynn Carroll

Pinetop Perkins

Bonnie Lee

Little Walter

Koko Tayler

Zora Young

How do I learn blues piano?

Blues Form

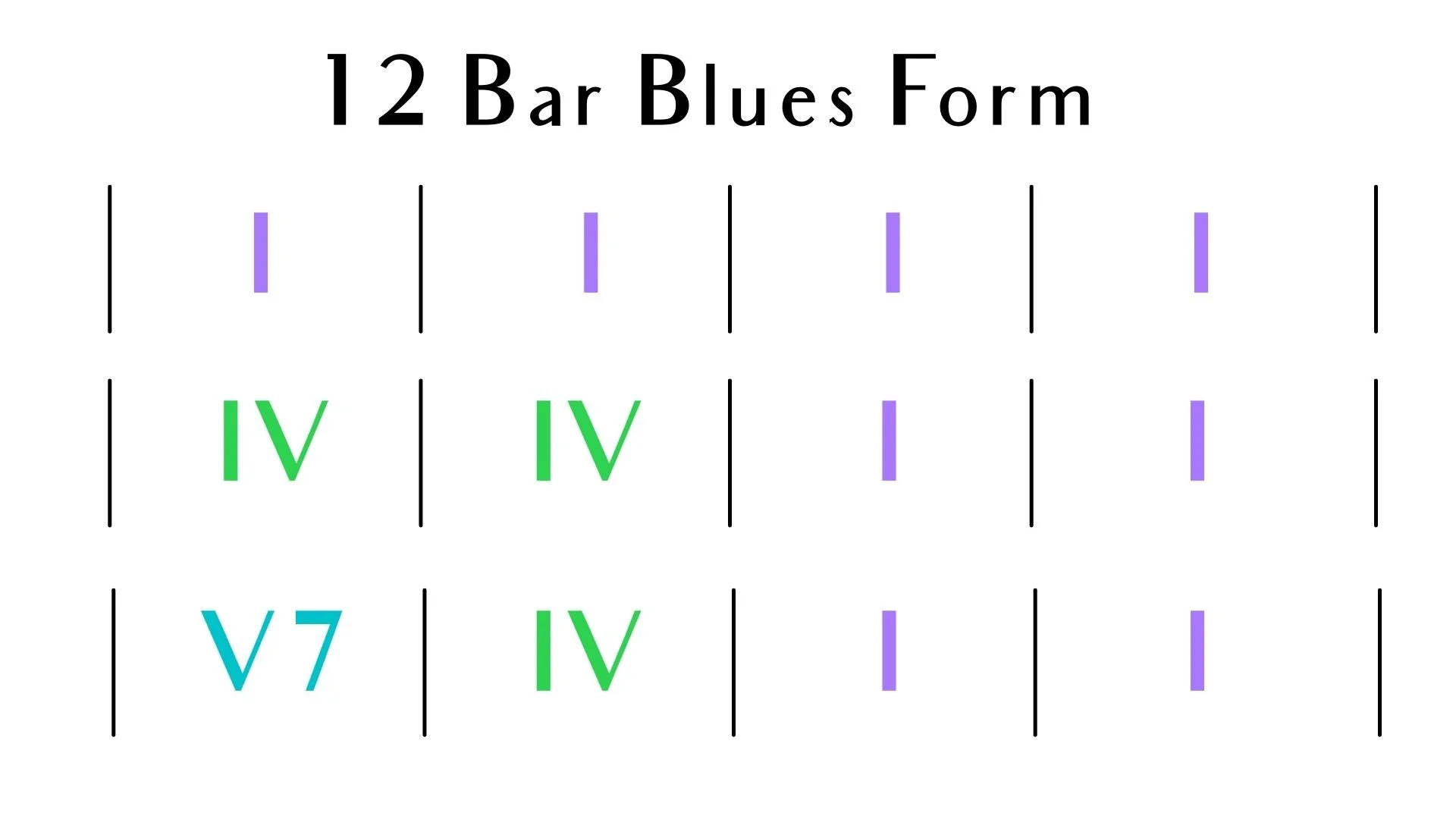

The first thing to know when you are trying to learn blues piano styles, or learn blues on any instrument for that matter, is how to follow the standard blues form. Blues comes in so many variations, but the most typical blues form that you will encounter is a 12 bar blues. This form has variations within it, but a basic 12 bar blues looks like the chart below, with many options for variation. This 12 bar blues is written using roman numerals as chord symbols. You will want to know your blues chords, and follow the blues chords written out in the form. This is the foundation to learn blues piano.

Learn how to play blues on piano in the self-study BLUES AND JAZZ YOU CAN USE course! Join the waitlist now to get a special discount.

If you are playing the blues on piano in the key of C, your blues chords will be:

I = C chord

IV = F chord

V7 = G7 chord

The classic 12 bar blues form, organized into three lines of four bars each. The blues chords are represented by color coordinated roman numerals.

As you learn blues piano styles, a few common variations that you might see in a 12 bar blues form will rearrange some of the blues chords. One alteration is changing the last I chord into what is known as the turnaround by playing a V7 blues chord instead. The turnaround creates a driving feel that makes you want to return to the beginning of the song again and again, and can help musicians keep their place in the form. In the video to the right, demonstrating how to play a blues on piano, you will here a turnaround at the end of the form. Another common blues chord substitution is to substitute a IV chord in for the second measure, in place of the I chord.

How to play a blues on piano

There are more complex variations that are used frequently, but this foundation for a 12 bar blues will get your started in learning how to play beginner blues piano styles, and learning your blues chords. There are also other blues forms, outside of a 12 bar blues as well. One is the 8 bar blues, which was a very early form used in blues music, and has fewer rigid harmonic rules around the blues chords while still contains many of the classic characteristics of blues music within its 8 bar form.

Blues Scale

The blues scale is the foundation for the characteristic blues sounds. “Blue notes” are the different altered pitches that show up in a blues scale. The blues scale is an integral part to learn blues piano styles. Many people approach soloing by saying, “just use the blues scale,” although that can still be to open ended, and we’ll unpack that below. There are actually different types of blues scales, although one is more ubiquitous than the other. Both variations of the blues scale are built on a minor pentatonic scale, containing the 5 scale degrees of 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7.

Believe it or not, the minor blues scale is the one that is considered universal, and can be played in most blues, jazz, and rock settings and fit in completely. This standard scale includes the pitches 1, ♭3, 4, ♭5, 5, ♭7. If you are learning blues piano styles for beginners, this is the only scale you need to know, and you can rely on it as you learn new melodies and start to learn blues piano improvisation. The major blues scale, in contrast, is used in major settings only, and contains the pitches 1, 2,♭3, 3, 5, 6. This is less common, and is best used for a distinct color change in your sound.

The best ways to learn blues piano scales in order to integrate them into basslines, comping patterns, and solos, is to play them in a variety of keys. These are also the best practices to learn jazz piano scales. Start with a key you are already playing a blues or jazz piece in, (or when in doubt, start in C!) and learn the blues scale. Play it one octave, up and down, with even notes. Then try swinging the rhythm, playing with a long short pattern. When that feels easy, try moving up and down the piano with more than one octave. Then try arpeggiating different patterns or variations of the scale. Invent a blues riff, and play it in different places on the piano. Finally? Do all of that in a different key! That’s when you know it’s really sunk in.

Want to learn more piano scales? This piano scales book lay the foundation for learning the best fingerings to use when playing major and minor piano scales.

Piano Scales Book10.00

Digital Piano Scales Book10.00

How to a comp chords on a piano

What is ‘comping’ on the piano?

The term “comping” is just a way of saying “accompaniment.” Now, piano players are almost always accompanying in some form or another, so when we learn blues piano styles and hear the word “comping” it specifically means the type of supporting harmonic patterns being played behind a soloist or used to vamp or fill in time and space in a piece of music. These patterns support harmonic movement, the rhythmic feel of the piece, and create distinctive textures. It is often perceived as the background of a blues or jazz performance, but comping is actually vital and challenging, full of foundational knowledge and constant improvisation and adjusting. This is a big step as we learn how to play blues on piano.

Blues Chord Building

Part of the process to learn blues piano styles is to learn to build blues piano chords. To build a chord, you will start with the root of your blues chords, which is also the name of your chord. If you are playing a C major chord, for example, your root is C. A triad is a chord containing three pitches. To build a basic triad in root position, with the root on the bottom, you will stack your intervals in thirds. So your C major triad is built on C, and also contains a third up, E, and another third up, G.

The images below model this process, and also show the need to notice whether you are using major or minor thirds as you build your chord. This will determine the quality of your overall chord. A major third on the bottom of your chord when it is in root position, and a minor third on top of your root position triad makes the over all chord a major chord. If these intervals were flipped, with the minor third on the bottom, again when in root position, and a major third on top, then it would be a minor triad.

Use the pages below from the Piano Progressions book to see how a basic root position triad is built.

It is common for blues chords and jazz chords to add sevenths to create some dissonance in our harmonies. To turn a triad into a seventh chord, find the note that is an interval of a seventh away from your root, or continue with your process of stacking in thirds until you have four pitches in your chord instead of three. Again, the major or minor third makes a difference. A major triad and minor seventh will create a dominant chord, while a major triad and major seventh create a major seventh chord.

To complicate things even more, blues chords and jazz chords will often add extra symbols and numbers meaning different things. Don’t panic! A triangle means major, a dash means minor. The numbers are what you would expect- an extra interval above the notes you are already playing. An “add 9” for example, means to add a ninth to your chord. If it says “sus,” then that chord will have a suspended pitch in place of the third, usually replacing the third with a fourth or a second.

Want to learn more about building chords? This Piano Progressions book breaks down the details of building major and minor chords, and adding 7ths and other altered pitches to chords. It even features examples of notated comping patterns at the end, to get you started reading chord charts and playing new patterns.

Digital Piano Progressions Book10.00

Chord Voicings

Piano has a really unique approach to chord voicings, and you’ll need to learn about chord voicings as you learn blues piano styles. Most instruments are limited by the range of the instrument, or the configuration of the instrument when it comes to what order to build chords in. A guitar may not play a root position chord, for example, because of the order in which the strings and pitches fall into place. Because piano is not limited by range, and all of the pitches are available to you at any time, we have the unique opportunity to rearrange the shape of the chord.

The primary strategy involved in choosing your chord voicings is deciding what inversion to use. An inversion is the configuration of the chord, which with triads includes root position, first inversion, and second inversion. I like to describe finding the inversions as flipping the chord, or scrambling it up. You can take the top note and put it on the bottom, or take the bottom note and put it on the top, and you will be playing a different inversion.

Some great ways to practice inversions as you learn how to play the blues on piano is to start with the root position chord, and invert it up and down the piano in each hand. Then, pick a chord progression, and try moving up and down the piano to the closest inversion of the next chord. Probably the simplest way to practice this skill is to simply play through a chord progression very slowly and find the absolute closest configuration of the next chord. A lot of finding chord voicings in blues piano styles comes down to listening and experimenting, and is a reflection of your own personal taste and style.

The more notes that are involved, the less obvious the inversions will be. This is where dropping non-essential pitches is handy, and frees up fingers that you can be playing melodic lines or generating rhythms with. When deciding which pitches to leave out, I look for notes that are already being played in the left hand, or are being played in the melody. If they already show up somewhere, then by playing it again, I would be doubling the note. It’s fine to double, but sometimes it is extra and redundant work. If no pitches are doubled, it’s usually fine to leave out the fifth, or if the root is played in the bass by you or a bass player, you can actually drop the root.

Blues Chord Patterns

Like chord voicings, the chord patterns that you choose to play will be informed from experience and experimenting, and will often be improvisatory, or in response to the style of the tune or the group that you are playing with. Creating and varying new chord patterns is a great way to learn simple blues piano improvisation. This will be trial and error while you are learning beginner blues piano. At times your hands will play blues chords together while you learn blues piano styles, and at other times they will contain completely contrasting parts of a song.

There are so many classic patterns of blues chords and blues basslines that you will recognize as distinct blues piano styles. In the video to the left, featuring a section of “St. Louis Blues,” you will hear and bluesy boom-chuck pattern. The boom-chuck feel is based on playing the root down low, and then part of the chord up higher. Sometimes you will alternate between the root and a low scale degree 5 for even more of a varied stylistic feel. This is a great style to play in country blues, and is often seen in ragtime styles and folk songs.

The video to the right of “Sweet Home Chicago,” features a style of accompaniment called the shuffle. With a constant pulsing of the swung eighth notes in the left hand, alternating between a pattern of a fifth and sixth, you can here the rhythmic drive of this style. The shuffle is a great accompaniment style for Chicago blues and other urban blues, as well as class rock and roll songs.

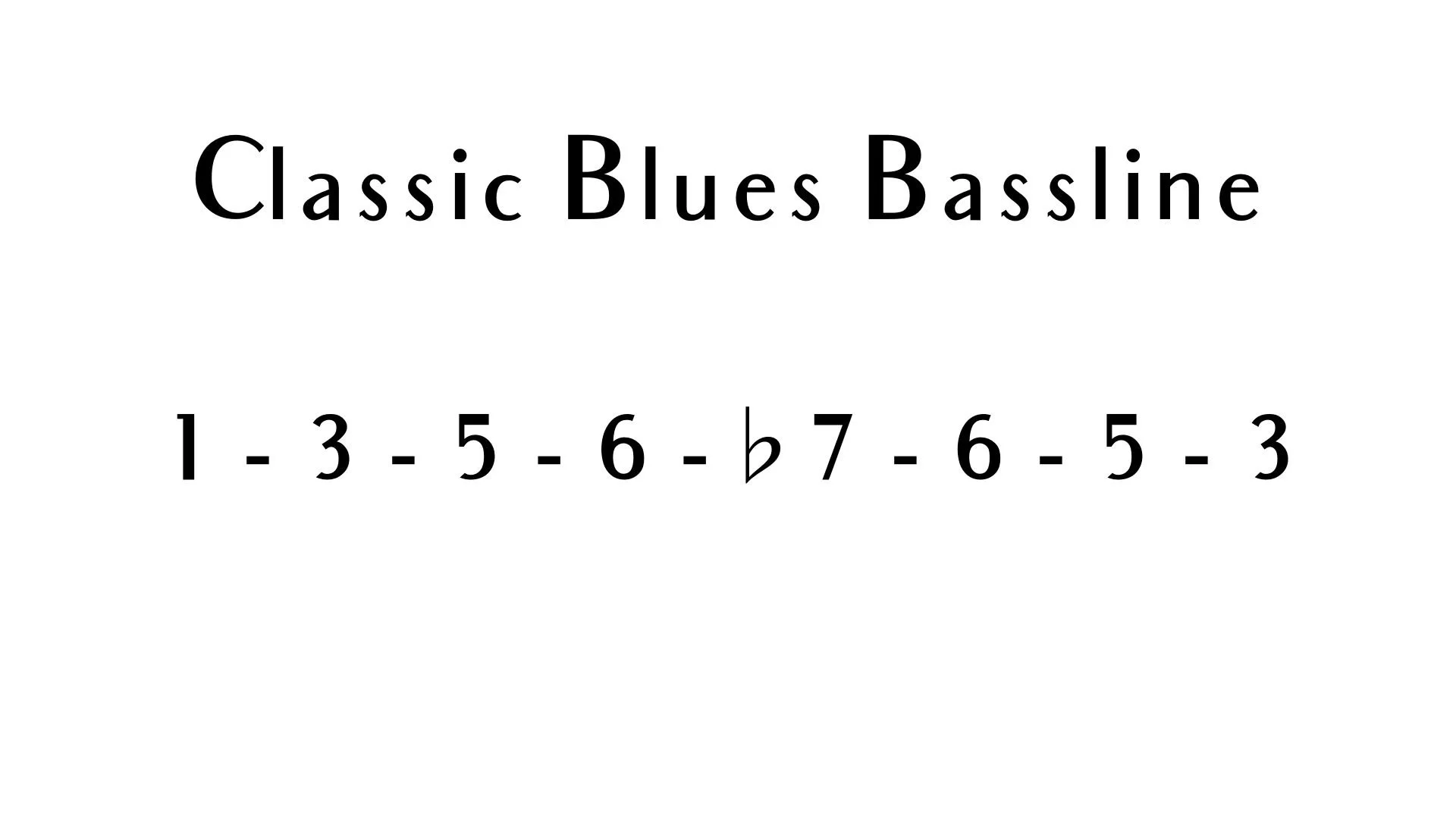

Blues Basslines

Piano is such a funny instrument. Part of the process to learn blues piano styles is to learn what a bass player would do, so that you can do it yourself. When building a bassline, the goal is usually to focus on the root of the chord. Oftentimes, you want to really emphasize that harmonic center on the downbeat, or beat one of the measure, at least when you are switching chords. When you’re getting started building basslines, start by playing through the form and holding the roots down in the left hand, and the chords in the right, to get the layout of the form. Next, start walking the bassline by outlining the notes in the triad: 1-3-5. I like walk up and come back down, playing 1-3-5-3, or a note for each beat of the measure in 4/4 time. A classic walking bassline is written out below, and will take up two full measures. That means you will vary your bassline when you get to the quick turnaround in the last four measures of the blues form.

There are so many different types of basslines outside of this, a whole new group for each different style or speed of the song. An example of a funky blues bassline breakdown is included here, with the bassline Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” as was transcribed by Anthony Rideout.

One really unique component of blues basslines is that there is quite an improvisatory approach to forming a bassline. Basslines are a great way to learn blues piano improvisation styles. Like finding voicings and rhythm patterns for comping, finding a bassline that you are happy with and return to again and again is a process of experimentation and listening. One really fun element of improvised basslines is finding creative ways to circle key pitches. For example, if I am getting ready to switch chords, I can really emphasize my new root by approaching is from a half step, or a few half steps away. This features a distinct chromaticism which really drives the harmony home.

Creating your own blues

How to apply these skills

The hands down best way to apply all of these skills and strategies when starting to learn blues piano is to practice them with a reliable backing track. We are so fortunate to have the aid of youtube, we can find these tracks for free in any key, any style, at any tempo. Use these to practice playing in blues form, and to apply new comping style ideas with blues chords, or to try developing new blues basslines. If you are lucky enough to have someone in your life who plays the blues, practicing along with another person is a great way to internalize all of these new blues piano techniques.

Listening to the blues

Any lifelong musician will tell you that listening to music is the secret to learning music. When you are starting to learn blues piano styles, it’s important to listen to examples of blues piano playing. It can feel difficult to make a study of the style you want to learn, and to listen intentionally. Music is like a language, though, and should be approached in a similar manner. You should be listening to the language you want to learn, and hearing it spoken fluently by an expert or native speaker. This will help you internalize your own inflections and accents to speak with.

Sometimes when we are new to a style, it is difficult to know where to start. At the top of this page, I included a lot of lists and images of names of incredible blues musicians to listen to in each style discussed. Of course, this list is not all encompassing, but it is a starting place for listening to different types of blues. Listen to different artists and see what you like. Start here, with this Spotify playlist of blues music.

Writing a blues

I love using composition as a tool not only for self-expression, but for learning and applying skills. If you have a general grasp of the basics of playing blues piano, and want a concentrated way to learn blues piano and get to know the style, this is a great method for developing that.

How to write a blues: first, pick the key you want to be in, and play the blues scale in that key, and play the 12 bar blues form in that key. Then, make up a blues melody! You can use lyrics, or not, whatever you are comfortable with. If you are using a 12 bar blues form, then your melody should follow AAB form. The first line is four bars long, then you repeat that melody so that it fits with the IV chord in the next line, before finishing with a B melody in the last line. Your B melody will need to fit with the V7, IV, and I chords at the end of the song. If you want to add lyrics, go for it! They also follow AAB form. Next, try to play or sing your melody while you play the chords that go with it. Be sure to write down or record your ideas so you don’t lose them. You can use this awesome musical notes journal for that.

Learn Blues Piano Improvisation

Everyone wants to learn blues piano improvisation, but it can be so intimidating! Like everything else in learning blues piano, it’s hard to know where to start.

Here’s my process to help you learn blues piano improvisation:

Start with the blues scale. Pick your key and play the scale to get familiar with it.

Put on a backing track and pick one note- I recommend the root. It sounds very basic, but trust me, this works. Play the blues backing track and practice soloing by making up rhythms with just one note. Do this until it feels fun and rhythmic, and you are comfortable with it.

Next up, add another note! Use the root and the lowered third, and do the same thing. Put the backing track and just play. There is no wrong answer. Move up and down the piano, to play with range. Let this feel silly and experimental.

Once that feels good, add one more. Let’s try the lowered seventh- but use the one below the root. Really! It will have a cool bluesy sound, and using just these three notes will give you a lot of options. You don’t have to use all three all the time. Try playing with just two at a time, or focusing on one note and occasionally sprinkling all three in.

Make this more challenging by playing chords in one hand, and improvising with the other. Eventually, you can add harmonies under your improvisation.

As you get more comfortable with this exercise, you can start adding other notes from the blues scale, or experimenting with different jazz modes. The most important thing when you want to learn blues piano improvisation is to keep it simple and easy at first, so that you can focus on expression and experimenting with playful sounds, rather than getting caught up with right and wrong. Just enjoy the process!

Learn how to play blues on piano in the self-study BLUES AND JAZZ YOU CAN USE course! Join the waitlist now to get a special discount.